Afghans encounter arduous mountain journeys for coronavirus tests

12 June, 2020

Villagers found in Arashakh Poen first heard about the coronavirus in March when a large number of men returned from Iran - residents of the community who had been employed in the neighbouring region, now trying to escape the newly declared pandemic.

What they didn’t know - and dreaded - was that that they had likely brought the virus house to their remote village in northern Afghanistan’s Takhar province, cut off from key roads by both mountains and a river.

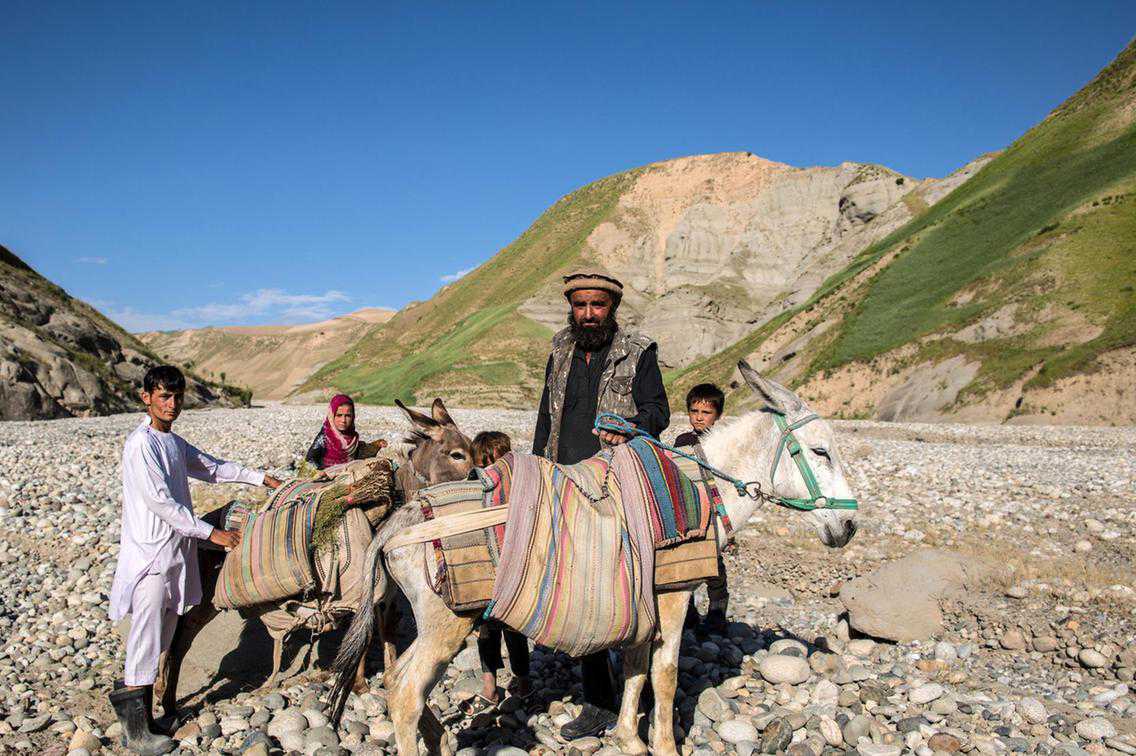

That’s so why when Khair Mohammed, 48, first developed symptoms that quickly grew worse, he faced a hardcore choice: residing at his residence, hoping to recover, or braving the voyage to Taloqan town - with the simply Covid-19 testing center in the province - in regards to a three-hour donkey ride through the mountains, accompanied by a bus trip.

Too weak to visit, he opted to stay put.

His gamble exercised and he recovered, but Mr Mohammed is merely one of an incredible number of Afghans residing in far-flung mountain villages, hours from roads and hospitals.

Afghanistan’s official Covid-19 infections have only passed 20,000, but with a test-positive rate at 40 percent, actual figures are deemed higher. With only eleven testing laboratories across the country, the capacity of Afghan authorities to monitor the propagate of the condition remains low.

“We’re along the way of establishing 20 more testing facilities, but even these will stay found in the provincial capitals,” explained Dr Qadir Qadir, the Ministry of Public Health’s standard director, adding that regardless if testing was ramped up, little would change for far-away communities.

At the moment, about 2,000 tests are evaluated in the country each day, but with up to 20,000 daily samples taken, laboratory staff are lagging behind, with result waiting circumstances often so long as two weeks.

Mr Mohammed’s village includes a lot to offer: a little coal mine up the hill will keep houses warm in winter; a salt mine supplies work for a number of the villagers and a close by river irrigates crops and farmland. Arashakh Poen’s mountain views are spectacular, but villagers have prolonged decried its remoteness: neither roads nor a clinic are nearby, limiting travel alternatives to lengthy hikes or uncomfortable donkey rides in summer months, while large snowfall in winter season forces the community to remain put for months at a time, disease or not.

Countless villagers have made the trip; some of them remaining in medical center to hold back for test benefits, while some returned home, but even after weeks there have been no updates on the infection status.

Dr Abdul Jamil Frutan, who works Taloqan’s coronavirus medical center, says that only test-positive patients are contacted, while no person is forced to remain at the clinic.

“Even those persons who made the trip to metropolis didn’t quarantine in their houses soon after,” Mr Mohammed admitted. “We’re farmers and pet keepers. In rural Afghanistan, you can’t just take a break. We work to survive.”

This resonates with other, equally remote communities.

In neighbouring Badakhshan province, Shakira Nuddin, 30, has only kept her village Khaja Gulrang for medical reasons, including to test for Covid-19 previous month, when she joined up with her brother and different villagers on a shopping visit to the city ahead of the Eid Al Fitr holiday.

“If indeed they hadn’t travelled already, presently there could have been no opportunity for me to keep,” she admitted. In her village, women don't travelling unaccompanied. The journey - several hours on a donkey via an empty river bed accompanied by a taxi ride, is normally exhausting.

From the main street, Badakhshan’s provincial capital Faizabad and Takhar’s capital Taloqan are almost at equal distance - Ms Nudddin’s family usually opts for Taloqan, a slightly bigger market city.

After taking the test, Ms Nuddin hardly ever heard again from the clinic. “Receiving examined was an exception,” the mother of four admitted, explaining that she previously hadn’t possibly left for childbirth. “We will be born in the village, and many of us die right here,” she added.

While the community have been informed about the virus and its own dangers - the two by men returning from working in Iran, in addition to by non-profit organisations employed in the province - the arrival of the pandemic has been neither a shock nor a surprise.

“We’ve been through diseases and war here. We had our houses washed aside by flash floods and we endure frigid winters with few information. A new virus is barely regarded as a threat,” she explained.

“Inside our village, we assume that lots of have previously passed the virus,” Khair Mohammed stated. “But living definately not any testing centres, almost all of us won't know.”

Source: www.thenational.ae

TAG(s):