California to apologize for internment of Japanese-Americans

17 February, 2020

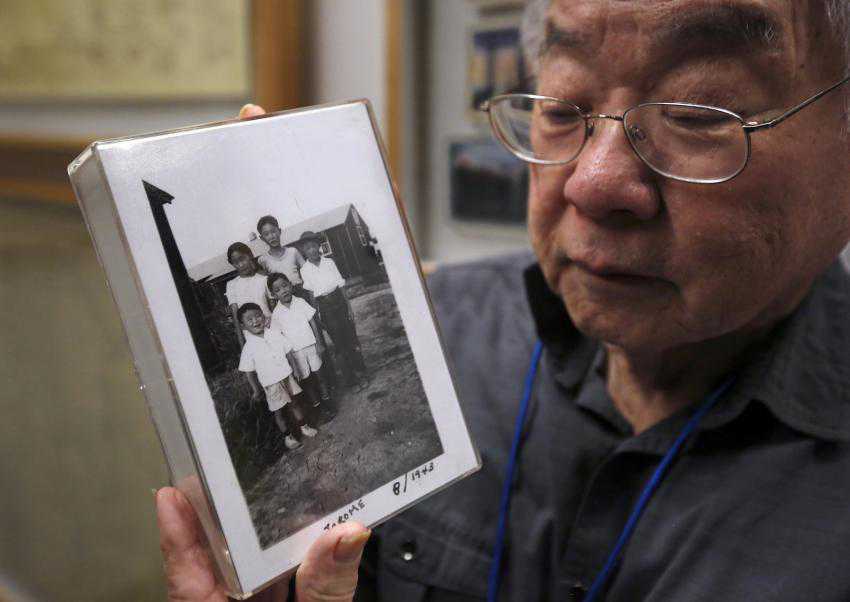

Les Ouchida was created an American just outside California's capital city, but his citizenship mattered little after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor and the United States declared war. Based solely on the Japanese ancestry, the 5-year-old and his family were extracted from their house in 1942 and imprisoned far away in Arkansas.

They were among 120,000 Japanese-Americans held at 10 internment camps during World War II, their only fault being “we'd the wrong last names and wrong faces,” said Ouchida, now 82 and living a short drive from where he was raised and was taken as a boy because of fear that Japanese-Americans would side with Japan in the war.

On Thursday, California's Legislature is expected to approve a resolution offering an apology to Ouchida and other internment victims for the state's role in aiding the U.S. government's policy and condemning actions that helped fan anti-Japanese discrimination.

President Franklin D Roosevelt’s executive order No. 9066 establishing the camps was signed on Feb 19, 1942, and 2/19 now could be marked by Japanese-Americans as a Day of Remembrance.

Assemblyman Al Muratsuchi was created in Japan and is one the roughly 430,000 persons of Japanese descent moving into California, the most significant population of any state. The Democrat who represents Manhattan Beach and other beach communities near LA introduced the resolution.

“We like to don't stop talking about how we lead the nation by example,” he said. “Unfortunately, in this instance, California led the racist anti-Japanese-American movement.”

A congressional commission in 1983 figured the detentions were a result of “racial prejudice, war hysteria and failure of political leadership.” Five years later, the U.S. government formally apologized and paid $20,000 in reparations to each victim.

The amount of money didn't come near replacing that which was lost. Ouchida says his father owned a rewarding delivery business with 20 trucks. He never fully recovered from losing his business and died young.

The California resolution doesn’t include any compensation. It targets the actions of the California Legislature at that time for supporting the internments. Two camps were situated in the state - Manzanar on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada in central California and Tule Lake near to the Oregon state line, the major of all camps.

“I want the California Legislature to officially acknowledge and apologize while these camp survivors remain alive,” Muratsuchi said.

He said anti-Japanese sentiment began in California as soon as 1913, when the state passed the California Alien Land Law, targeting Japanese farmers who some in California's massive agricultural industry regarded as a threat. Seven years later the state barred a person with Japanese ancestry from buying farmland.

The internment of Ouchida, his older brother and parents started in Fresno, California. 90 days later they were delivered to Jerome, Arkansas, where they stayed for almost all of the war.

Given their young ages at that time, many living victims such as for example Ouchida don’t remember much of life in the camps. But he does recall straw-filled mattresses and little privacy.

Communal bathrooms had rows of toilets with no barriers between users. "They put a bag over their heads if they went to the bathroom” for privacy, said Ouchida, who teaches about the internments at the California Museum in Sacramento.

Prior to the last camp was closed in 1946, Ouchida's family was shipped to a facility in Arizona. When the family was freed, they took a Greyhound bus back again to California. When it reached an end sign near their community outside Sacramento, “I still remember the women on the bus started crying,” Ouchida said. “Because these were home.”

The resolution, co-introduced by California Assembly Republican Leader Marie Waldron of Escondido, makes a passing mention of “recent national events” and says they serve as a reminder “to understand from the mistakes of days gone by.”

Muratsuchi said the inspiration for that passage were migrant children held in U.S. government custody over the past year.

Ouchida said Japanese families like his always considered themselves loyal citizens before and after the internments. He holds no animosity toward the U.S. or California governments, choosing to concentrate on positives outgrowths like the everlasting exhibit at the California Museum that delivers an unvarnished view of the internments.

"Even if it took time, we've the goodness to still apologize," he said.

Source: japantoday.com

TAG(s):