'Can I recycle this?'

21 November, 2021

“Can I recycle this?” Who among us hasn’t stood over our recycling bin, clean container in-hand, asking ourselves this very question? When it comes to plastic, the little symbol on the container makes things even more complicated.

Then, there is the news. A “Planet Money” podcast from 2020 exposed a hand-in-hand relationship between the plastic and oil industries, who, along with the chemical industry, worked in backhanded ways to keep plastic recycling down. Producing plastic, a petroleum-based product, requires massive amounts of crude oil, and so new plastic was much better for these large corporations’ bottom lines, while recycled plastic was a threat. Decades ago, the plastics industry slapped recycling labels on their products while they had no plan in place to follow through on actually recycling them; they just wanted consumers to feel good about plastic.

Reporting has also shown during recent years that recycling plastic is more expensive than it’s worth, or that, worse, it just gets thrown away at the sorting facility anyway. And we’ve all seen the images of and heard the stories about the gigantic island of plastic floating in the ocean.

In many of these news stories, this figure gets tossed around a lot: Less than 10% of the plastic ever made has actually been recycled.

It all makes a person wonder, while standing over their recycling bin, not only is this recyclable, but is there any point to recycling it?

“There is this feeling of distrust,” says Michele Morris, with Chittenden Solid Waste District, of the plastics recycling industry. That’s been exacerbated by what she says are over-generalizations in reporting by outlets like National Public Radio, American Public Media, New York Times, National Geographic and Planet Money on recent wrong-doings in plastic recycling. Of course, she acknowledges, “these things have happened, but not here in Vermont.”

Josh Kelly, who is with the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources, says, “the public is having a wrestling moment with plastic.” He says he recently heard a speaker at a conference say “plastics have lost their social license,” and that point resonated with him.

Morris shares a similar sentiment: “Everybody is rightly concerned about plastics,” she says, because their use is increasing, they take raw resources to make, they last a very long time, and we’re not yet sure what happens when they break down.

But when it comes to recycling plastic here in Vermont, says Morris, if you put it in the blue recycling bin, and if it is clean and truly recyclable, it is being recycled. She says, in short, yes, plastic is being recycled; no, it is not being thrown away; and yes, it’s helping.

In fact, she and others say, Vermonters have a recycling record they can be proud of.

At the state’s two material processing facilities, also called MRFs, trucks come in and dump mixed recyclables right on to the floor. Vermont has a single-stream recycling program, meaning glass, cans, plastic, paper and cardboard can all go together in the same bin, and then they’re separated out at the MRF. Then, the materials are processed and sold to be made into new products.

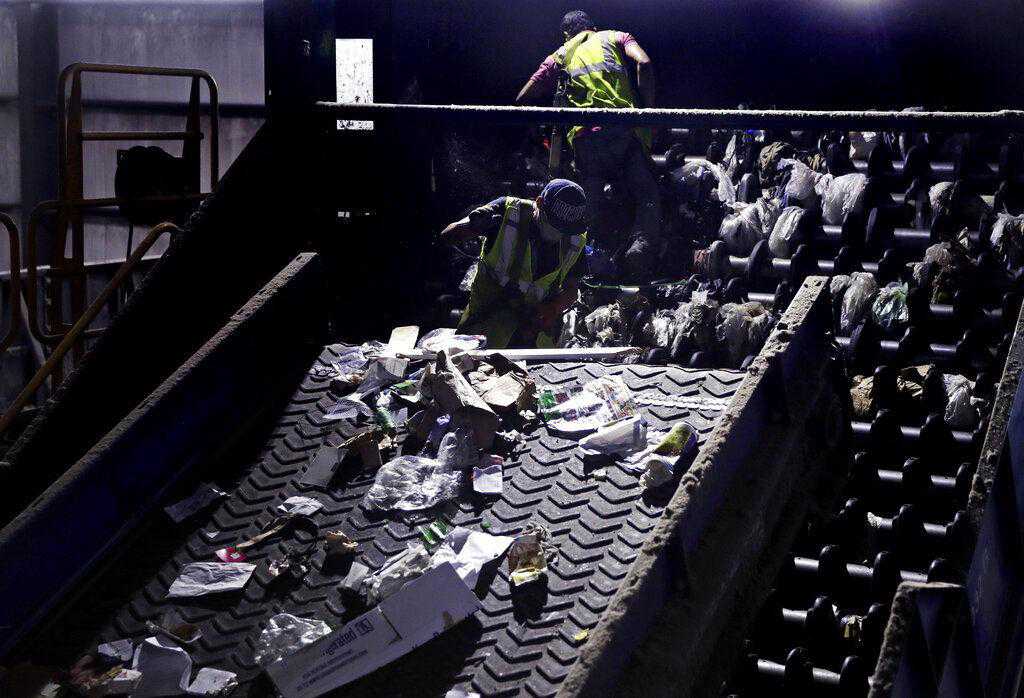

There at the facilities, which are located in Rutland and Williston, a skid-steer is used to push the recyclables onto the conveyor belt, right at the floor level, and from there the yogurt containers, milk jugs, glass jars and shipping boxes go through a series of steps to sort them by material: First, two-dimensional materials like cardboard are flung off the conveyor belt by what looks like a series of spinning paddles, then heavy items like glass jars sink out of the stream, while lightweight paper is blown off, and magnets are used to pull out the metal.

As the remaining materials, including plastic, continue along a series of conveyor belts, real, live people working at the facility pick off the recyclable plastic containers to be sorted by type of plastic and then processed. These plastic bottles, jugs, containers and clamshells will be made into flakes, pellets or fiber, sold on a global commodity market and then made into other useful products like toys, fleece, or plastic “lumber” for decking material, for example. They’re highly valuable products that both Morris and Kelly point out would never be thrown away instead of sold; in the case of one type of plastic, it’s currently more valuable than recycled aluminum.

At the plant, the workers will also pull off things that will gunk up the whole system, like plastic bags or strings of Christmas lights, neither of which are recyclable at this facility in the first place. What’s left is a small stream of unrecyclable material that gets landfilled, and this is made up of things such as unclean containers, like dirty peanut butter jars, and items that were not truly recyclable to begin with. Amazingly, that last category has included garden hoses, pots and pans, deer guts, fireworks, a lawnmower engine, and one time, unbelievably, a hand grenade.

Overall, though, it’s a system that works well: Vermont’s MRFs recycle 93% of the material that comes in, while only 7% ends up in the landfill. Those figures are far better than other states, and this high rate of success is in large part due to individuals doing their part to recycle the right things, in the right ways. A statewide network of waste management districts, like the one Morris works with, help with education and outreach, too.

But what about that 10% figure? It turns out, there is a bit of nuance. For one, the analysis that led to this quotable figure included all plastic ever made, since 1955, and many of those products were produced before reduce, reuse and recycle programs became mainstream. Also, it’s also important to remember that plastic is not just water bottles, laundry detergent containers and yogurt tubs. Plastic goes into car parts like dashboards, bike parts, tarps, house wrap used in home construction, plastic picture frames, printers, medical and dental supplies, and so much more.

Unfortunately, that nuanced figure can do more harm than good, by having the effect of reducing consumer confidence in recycling.

“Yeah, it’s accurate,” says Kelly of the 10% figure. “But does it mean you shouldn’t recycle that milk jug? No. There is 99% chance that jug will get recycled.” He adds that he’s making up that 99% figure, but you get the point.

Besides, Morris and Kelly point out, this focus on plastics is missing the big picture. They both refer to the state’s data that shows plastic, by weight, is one of the smaller waste streams going into our MRFs. Paper and cardboard, on the other hand, make up the largest portion of our recyclable waste stream entering these facilities, at about 70%, by weight, combined. But plastic, despite being a small portion of our recyclable waste stream, has the greatest need for clearing up any misunderstandings when it comes to recycling.

At the beginning of our conversation, Kelly told me, “If I have one job, it’s to get confidence in recycling back.” As we wrapped up, I brought our conversation back to the person standing over their recycling bin, clean container in hand, asking themselves what is the right thing to do.

“As long as you’re focusing on recycling the right things,” says Kelly, “like clean and dry paper, and empty bottles, cans and jugs, you’re doing a good thing for Vermont recycling.”

Then, there is the news. A “Planet Money” podcast from 2020 exposed a hand-in-hand relationship between the plastic and oil industries, who, along with the chemical industry, worked in backhanded ways to keep plastic recycling down. Producing plastic, a petroleum-based product, requires massive amounts of crude oil, and so new plastic was much better for these large corporations’ bottom lines, while recycled plastic was a threat. Decades ago, the plastics industry slapped recycling labels on their products while they had no plan in place to follow through on actually recycling them; they just wanted consumers to feel good about plastic.

Reporting has also shown during recent years that recycling plastic is more expensive than it’s worth, or that, worse, it just gets thrown away at the sorting facility anyway. And we’ve all seen the images of and heard the stories about the gigantic island of plastic floating in the ocean.

In many of these news stories, this figure gets tossed around a lot: Less than 10% of the plastic ever made has actually been recycled.

It all makes a person wonder, while standing over their recycling bin, not only is this recyclable, but is there any point to recycling it?

“There is this feeling of distrust,” says Michele Morris, with Chittenden Solid Waste District, of the plastics recycling industry. That’s been exacerbated by what she says are over-generalizations in reporting by outlets like National Public Radio, American Public Media, New York Times, National Geographic and Planet Money on recent wrong-doings in plastic recycling. Of course, she acknowledges, “these things have happened, but not here in Vermont.”

Josh Kelly, who is with the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources, says, “the public is having a wrestling moment with plastic.” He says he recently heard a speaker at a conference say “plastics have lost their social license,” and that point resonated with him.

Morris shares a similar sentiment: “Everybody is rightly concerned about plastics,” she says, because their use is increasing, they take raw resources to make, they last a very long time, and we’re not yet sure what happens when they break down.

But when it comes to recycling plastic here in Vermont, says Morris, if you put it in the blue recycling bin, and if it is clean and truly recyclable, it is being recycled. She says, in short, yes, plastic is being recycled; no, it is not being thrown away; and yes, it’s helping.

In fact, she and others say, Vermonters have a recycling record they can be proud of.

At the state’s two material processing facilities, also called MRFs, trucks come in and dump mixed recyclables right on to the floor. Vermont has a single-stream recycling program, meaning glass, cans, plastic, paper and cardboard can all go together in the same bin, and then they’re separated out at the MRF. Then, the materials are processed and sold to be made into new products.

There at the facilities, which are located in Rutland and Williston, a skid-steer is used to push the recyclables onto the conveyor belt, right at the floor level, and from there the yogurt containers, milk jugs, glass jars and shipping boxes go through a series of steps to sort them by material: First, two-dimensional materials like cardboard are flung off the conveyor belt by what looks like a series of spinning paddles, then heavy items like glass jars sink out of the stream, while lightweight paper is blown off, and magnets are used to pull out the metal.

As the remaining materials, including plastic, continue along a series of conveyor belts, real, live people working at the facility pick off the recyclable plastic containers to be sorted by type of plastic and then processed. These plastic bottles, jugs, containers and clamshells will be made into flakes, pellets or fiber, sold on a global commodity market and then made into other useful products like toys, fleece, or plastic “lumber” for decking material, for example. They’re highly valuable products that both Morris and Kelly point out would never be thrown away instead of sold; in the case of one type of plastic, it’s currently more valuable than recycled aluminum.

At the plant, the workers will also pull off things that will gunk up the whole system, like plastic bags or strings of Christmas lights, neither of which are recyclable at this facility in the first place. What’s left is a small stream of unrecyclable material that gets landfilled, and this is made up of things such as unclean containers, like dirty peanut butter jars, and items that were not truly recyclable to begin with. Amazingly, that last category has included garden hoses, pots and pans, deer guts, fireworks, a lawnmower engine, and one time, unbelievably, a hand grenade.

Overall, though, it’s a system that works well: Vermont’s MRFs recycle 93% of the material that comes in, while only 7% ends up in the landfill. Those figures are far better than other states, and this high rate of success is in large part due to individuals doing their part to recycle the right things, in the right ways. A statewide network of waste management districts, like the one Morris works with, help with education and outreach, too.

But what about that 10% figure? It turns out, there is a bit of nuance. For one, the analysis that led to this quotable figure included all plastic ever made, since 1955, and many of those products were produced before reduce, reuse and recycle programs became mainstream. Also, it’s also important to remember that plastic is not just water bottles, laundry detergent containers and yogurt tubs. Plastic goes into car parts like dashboards, bike parts, tarps, house wrap used in home construction, plastic picture frames, printers, medical and dental supplies, and so much more.

Unfortunately, that nuanced figure can do more harm than good, by having the effect of reducing consumer confidence in recycling.

“Yeah, it’s accurate,” says Kelly of the 10% figure. “But does it mean you shouldn’t recycle that milk jug? No. There is 99% chance that jug will get recycled.” He adds that he’s making up that 99% figure, but you get the point.

Besides, Morris and Kelly point out, this focus on plastics is missing the big picture. They both refer to the state’s data that shows plastic, by weight, is one of the smaller waste streams going into our MRFs. Paper and cardboard, on the other hand, make up the largest portion of our recyclable waste stream entering these facilities, at about 70%, by weight, combined. But plastic, despite being a small portion of our recyclable waste stream, has the greatest need for clearing up any misunderstandings when it comes to recycling.

At the beginning of our conversation, Kelly told me, “If I have one job, it’s to get confidence in recycling back.” As we wrapped up, I brought our conversation back to the person standing over their recycling bin, clean container in hand, asking themselves what is the right thing to do.

“As long as you’re focusing on recycling the right things,” says Kelly, “like clean and dry paper, and empty bottles, cans and jugs, you’re doing a good thing for Vermont recycling.”