China’s supercharged new-energy sector is propping up exports, but will it last?

09 May, 2023

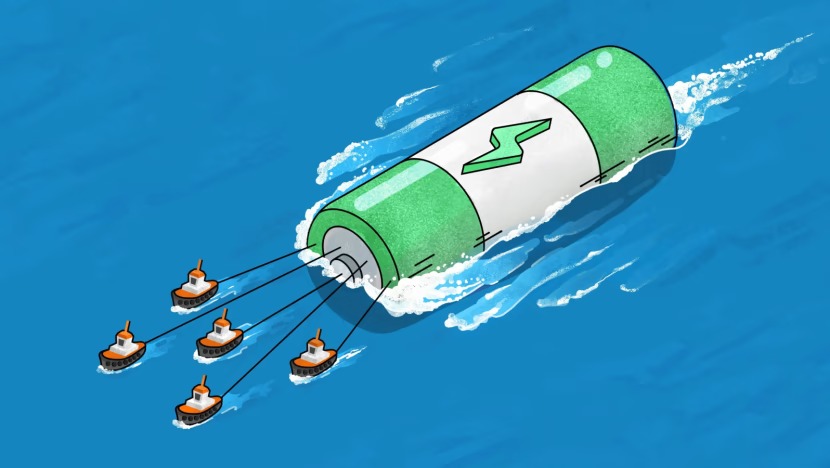

China’s shipment value of electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries and solar batteries surged by 54.8 per cent in US dollar terms during the first quarter, year on year

An intensifying deglobalisation of new-energy supply chains is underway, but analysts say it will not be easy to dethrone China as the dominant market player

For tens of millions of workers in China’s massive export sector, the surprising 14.8 per cent year-on-year growth in shipments in March is nothing but a figure when – as they see it – empty containers have been piling up at ports for months, and small manufacturers have struggled to stay afloat.

But the new-energy industry seems to be an exception. At China’s biggest automotive terminal in north-east Shanghai, thousands of electric cars are loaded onto shipping vessels every day, bound for destinations across the world.

This boom comes as authorities in the so-called world’s factory are increasingly pinning hopes on new-energy products – electric vehicles (EVs), lithium-ion batteries and solar batteries – becoming critical cogs in the engine of its export sector.

After all, China’s traditional export pillars, including apparel and furniture, are increasingly being relocated to other developing countries, such as Mexico and parts of Southeast Asia. According to data from China Customs, the outbound shipment value of EVs, lithium-ion batteries and solar batteries surged by 54.8 per cent in US dollar terms during the first quarter, year on year, reaching US$38.5 billion. And their share among all of China’s exports increased to 4.7 per cent in the quarter, from 3 per cent a year earlier.

As most of the world is embracing a green-energy transition to reduce the effects of climate change, Chinese companies have unquestionably become global market leaders in these industries, owing largely to government support and the nation’s vast manufacturing capacity.

But some industry insiders have raised questions about whether the robust export momentum can be sustained, with the low base effect fading, especially as excessive-capacity issues have already begun surfacing in China, coupled with what analysts say is an intensifying deglobalisation of relevant supply chains.

“The prices of raw materials (in the new-energy sector) have kept falling for the past few months. Many feel the whole market will soon reach – or has already got to – its peak,” said Xu, a logistics professional specialising in exports of new-energy products, who asked that only his surname be used.

“The current inventory is too large and cannot be sold out even in the next three years – from raw materials to the final products – everyone in the industry knows that,” said Xu, who is based in Jiangsu province north of Shanghai.

Julia Vorontsova, the founder and CEO of the Belgium-based Innovation Park, which connects companies with sources of funding, said that while the Chinese government has historically provided support for industries experiencing overcapacity, to help them maintain competitiveness, the future market shares in the new-energy sector may be influenced by various external factors, such as technological advancements, government policies and competition.

“Many countries, including the United States, European nations and South Korea, are investing heavily in the development and production of EVs, solar technologies and advanced batteries,” Vorontsova said.

“For global competition, this could lead to a more diversified global market.”

For the solar industry in particular, concerns over future export momentum are nothing new.

Although China’s total solar-product exports increased by more than 80 per cent in 2022, year on year, the monthly export value peaked in July.

The declining trend was finally reversed in the first quarter of this year, with the solar-product exports increasing by 16 per cent, year on year, thanks to a surge in shipments to Europe, which is China’s biggest overseas market for solar products and which accounted for 55 per cent of the nation’s total export value in 2022.

But concerns over future demand from Europe in the short term remain, due to a shortage of labour installing the modules.

According to Taiwan-based solar consultancy InfoLink, Europe imported 86.6 gigawatts worth of solar modules from China last year – more than twice the quantity that the continent actually installed in 2022.

For the EV and lithium-ion-battery sectors, the chill started being felt by industry insiders at the beginning of this year.

In southern Jiangsu’s Changzhou, a city known for having China’s most complete supply chain of EV batteries, many factories have been scaling back their production and workforces, according to Xu.

The sluggishness stands in sharp contrast to the frenzy seen among battery and EV makers since early 2021, as they rushed to secure raw materials and drove up the price of lithium carbonate – an essential material in battery production – tenfold.

But the price of lithium carbonate has plummeted by nearly 70 per cent since November, and the phasing out of a national subsidy scheme for electric-car buyers this year has triggered a fierce price war among major EV makers, with hefty discounts.

“I feel that the industry already reached its peak last year,” Xu said. “Another round of explosive growth seems quite unlikely.”

While tapping further into the overseas market is the most effective way to solve the overcapacity, the biggest uncertainties in the industry are also coming from abroad, as China’s monopoly in the sector has sparked more and more concerns amid rising geopolitical tensions.

The country’s share in all the key manufacturing stages of solar panels exceeds 80 per cent, and more than three-quarters of the world’s production capacity for batteries – which make up 40 per cent of a typical EV’s sticker price – is in China.

Meanwhile, the governments of all major developed economies are seeking to change the status quo through protective legislation and subsidies.

In June of last year, Washington’s Uyghur Forced Labour Prevention Act effectively blocked American imports of all products wholly or partially sourced from Xinjiang, the western region where China has been accused of committing human rights abuses against Uyghur Muslims and other minorities – allegations that Beijing has repeatedly denied.

Xinjiang produces about half of the world’s polysilicon – a critical material in solar-panel production.

Then in August, the Inflation Reduction Act was passed to support American EV producers by declaring that vehicles made with battery components manufactured in “foreign entities of concern”, including China, would be ineligible for tax credits after 2024. And from 2025, vehicles with any critical minerals from such entities will also be ineligible for tax credits.

Such actions have eroded the historical advantage of Chinese components, which are typically cheaper than components produced elsewhere, according to Chris Robinson, senior director of Boston-based Lux Research, which offers tech-enabled findings and advisory solutions.

“The theme of the year in the energy transition is deglobalisation,” he said. “Every region is focused on spurring the development of supply chains for key materials and technologies for the energy transition.”

In March, the European Union announced two cornerstone proposals of its Green Deal Industrial Plan – the Net Zero Industry Act and Critical Raw Materials Act – that will help push the region’s own manufacturing capacity on green technologies such as solar panels and batteries to at least 40 per cent of its deployment needs by 2030.

More threats are likely to surface in the long term amid the intensifying efforts by Washington to cripple China’s ability to produce advanced computer chips, said Lin Han Shen, senior adviser at the Asia Group consulting firm in Shanghai.

But China’s traditional strengths in mass production, and its ability to sustain losses longer to achieve dominant market positions, remain unhindered, Lin said, noting how this will make deglobalisation a lengthy process.

“In the foreseeable future, China’s dominance in the EV, solar and lithium battery space will grow because of its advantage of competing at lower price points and increasing control of the respective global supply chains,” Lin said.

Liu Wei, a partner at Pinsent Masons in Shanghai, said multinational car companies such as Volkswagen, Mercedes and Ford are among those taking rapid steps to electrify vehicles. And this push, Liu said, could eventually threaten the current market positions of Chinese EV makers such as Nio, Li Auto and Xpeng.

“But in terms of batteries and some specific new-energy sub-sectors like battery separators, electric valves, photovoltaic inverters, relevant Chinese companies will remain global market leaders for quite some time,” Liu said.

Still, leading Chinese companies in the green sector – from lithium-ion battery giant CATL to solar panel manufacturer JinkoSolar – have been deploying new manufacturing bases in the United States and European Union to circumvent any potential import restrictions that can be imposed by major foreign markets. And this means that the share of exports from China will inevitably go down.

Even if no geopolitical factors were in play, there would continuously be a shift toward the localised produce of new-energy products, according to Sam Abuelsamid, principal e-mobility analyst with Guidehouse Insights in Detroit, the US’ so-called Motor City.

“With automakers aiming to reach carbon neutrality, a key part of that effort is taking emissions out of the supply chain,” he said.

“Transporting lithium from Chile to China for processing, and then to North America or the EU for cell production, adds a lot of transportation emissions.”

Useful Links:

Source: www.channelnewsasia.com