Nato membership for Ukraine a key question at Vilnius summit

11 July, 2023

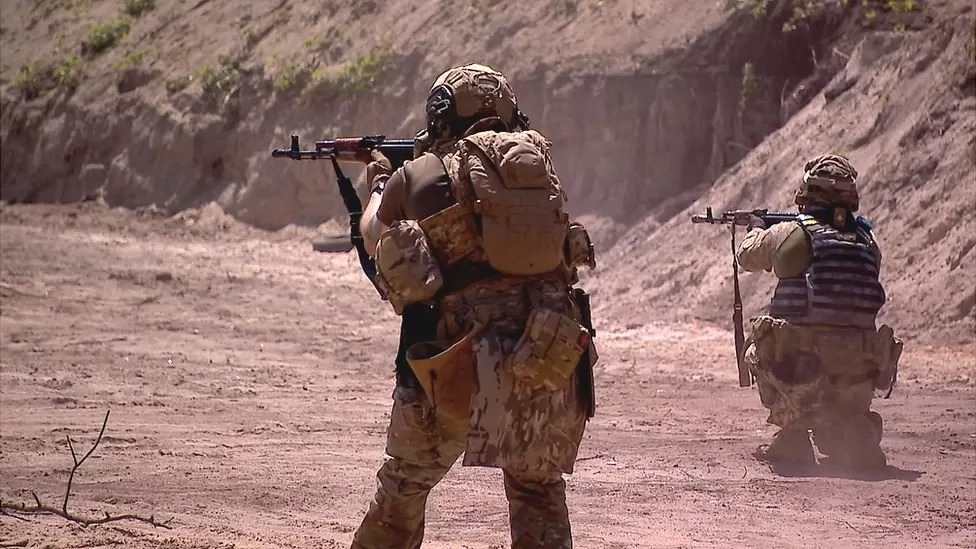

Out in a dense forest in central Ukraine, troops from a Ukrainian artillery battery are training before heading out to the front lines.

For some it will be a return to the fight, for others it will be their first time - as they replace those who have been injured or killed.

Firing at targets in a clearing with AK-47 rifles, they are careful to conserve ammunition. And it is not just training camps where supplies are low.

"We have enough fighting spirit to win, of course. Unfortunately, we currently do not have enough weapons," Roman, their commander, tells me. "The main thing is to have enough ammunition."

Out on the front lines they are having to economise, he explains. "This is not a secret. The amount of ammunition that the enemy uses daily is at least five times higher than the amount of ammunition that we use." Supplies from allies have been essential for Ukraine in this war. For Roman and other soldiers, the Nato summit in Vilnius is a crucial moment to ensure they have what they need to continue the fight.

The widespread expectation is that new weapons will be promised at the summit, as well as more supplies of ammunition. The US decision to provide cluster munitions from existing stockpiles last week was partly to act as a stop-gap before new artillery supplies are ready.

But viewed from Ukraine the summit is about much more than just weapons and ammunition - it is about what type of commitment the country will be offered when it comes to joining the alliance.

Ukraine has been knocking at Nato's door for years. What it wants is more than just positive noises and a feeling of being left in a permanent waiting room.

At the core of Nato is Article 5, which sets out that an attack on one member is an attack on all. This principle of collective defence could offer protection for Ukraine, but - almost everyone agrees - is very difficult to put in place when a country is already at war.

"We believe that it is long overdue to invite Ukraine to Nato," Oleg Nikolenko, a spokesperson for Ukraine's foreign affairs minister, says.

"An invitation to join Nato does not mean an immediate membership in Nato. We are cognizant of the fact that as long as the war goes on, Ukraine won't be able to join Nato. But we are talking about the invitation and setting the clear timeframe for this to happen."

The 2008 Nato summit in Bucharest casts a long shadow. Ukraine, along with Georgia, was told membership was on the cards in the future - but with no clear path and no expectation that it would be anytime soon.

That angered Russia but without offering any protection in return. Georgia was attacked in 2008 by Russia, and Ukraine attacked too - first in 2014 and then in 2022. Many of those US officials involved in the decision in Bucharest now acknowledge it was a mistake.

This time Ukraine wants greater clarity and concrete assurances. The exact nature and timetable of any commitment could have real consequences for the war. For instance, offering membership only when the war is over might encourage Russia to maintain a low level conflict to stall membership, some analysts argue.

But there are existing Nato members who are cautious about offering too much to Ukraine now. They fear this could draw Nato closer to war with Russia.

That is a view that is met with some annoyance in Ukraine.

"Let's be honest: for a long time, Nato has been paying too much attention to whether Russia will allow them to do anything," Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser to the office of the President of Ukraine, told me when I visited his heavily guarded office in the centre of the capital.

"Nato must say unequivocally that there are no more preconditions for this related to Russian threats."

Ukrainians view membership as a way to end the war by deterring Russia rather than escalating it. They acknowledge, as US President Joe Biden has made clear in recent days, that Ukraine needs to make the reforms that any prospective member has to undertake.

But they argue that Nato was set up to confront Moscow in the Cold War and yet it is now Ukraine which is effectively fighting on Nato's behalf, defending its eastern flank against Russia with its soldiers and civilians dying every day.

For many in Kyiv, the focus by some inside the alliance on the risks of an invitation are a mistake. What, they ask, are the risks of not acting?

In public, Ukrainian officials are careful to sound optimistic and not to enter into any discussion of the consequences if they receive only vague promises and looser "security guarantees". They do not want to sound ungrateful for the weapons and ammunition they still need right now.

But privately officials worry that in the long term a failure to bring Ukraine into closer alignment with the West will be used by Moscow to push a narrative within the country that Ukraine has been let down and the West cannot be trusted. People could feel betrayed, one senior official told me.

Without formal membership, the fear is the West could tire of supplying the weapons and ammunition Ukraine needs as the war grinds on. That is something Vladimir Putin and Russia is counting on.

So in Kyiv do they worry about that?

"I have a counter question: what does it mean to be tired of supporting Ukraine?" presidential adviser Mykhailo Podolyak remarks when I put that question to him.

"This means that democracy does not know how to defend itself. And that any authoritarian country, if it has a capacity to fight, will always win."

Source: www.bbc.com