Oud to joy: Inside one man's journey to hear the famed instrument

11 May, 2019

I am lost and hoping for a sweet sound to rescue me. I have specifically sought out this confusing, foreign environment, in search of an instrument that has long intrigued me.

My curiosity was first piqued in Andalusia in southern Spain. Those memories returned to me three years later in a museum in Belgium. Now I am in Morocco, adrift in the narrow, twisting alleys of the old town of Fes.

The sound I am seeking never arrives. Fortunately, it is not necessary. Of my own accord I manage to find the restaurant I am looking for, the setting for a rooftop rendezvous. As I climb a staircase to the third-floor terrace of this venue, I hear one low note; a single plucking of a string. Then comes a second, this one generating a higher tone. By the time a third note floats through the air, I am walking out on to the terrace. I finally come face to face with an oud player.

A history of the oud

Variously called the “sultan of instruments” and the “grandfather of the guitar”, the oud has helped shaped world music like few other instruments. Still used in modern Arabic music, this pear-shaped, short-necked, stringed instrument was a precursor to the guitar, which it pre-dates by up to 3,000 years.

The modern guitar, one of the most influential instruments across the world, was only invented in the late 14th century. The oud, meanwhile, is widely believed to date back to the time of the Kassites, the dynasty that ruled Babylonia from 1531 BC to 1155 BC, an area now within the borders of Iraq.

Unlike the European lute, the oud does not have frets, the raised lines along the neck of the lute and the guitar, in between which a player presses its strings. The absence of frets means an oud player can be more experimental, sliding along the strings from one key to another, or using the rapid variations in pitch known as vibrato.

The oud player also has fewer strings to work with. While a lute commonly has up to 24 strings, ouds tend to boast between 10 and 13. Rather than the short, thick pick used to strum a guitar, an oud player uses a longer, narrower plectrum, or a bird’s feather.

The musician credited with introducing the use of a quill to play the oud, and with increasing its number of strings, is the reason I first became acquainted with the instrument. I have wanted to see the oud played live since I first learnt about it in the Andalusian city of Seville. As I sat in my hotel there, thumbing through a book on the history of southern Spain, I came across a story that gripped me. It was about a “blackbird”. That was the nickname, translated from the Arabic word “ziryab”, given to Abul-Hasan Ali Ibn Nafi, the Iraqi musician credited with introducing the oud to Europe.

Ziryab left Baghdad in 822 AD and became a renowned entertainer in Al-Andalus. This area of Spain’s Iberian Peninsula was under Islamic rule for almost 800 years up until the late 15th century AD. Thankfully, he was in the correct place at the correct time. Abd ar-Rahman II, the fourth ruler of Al-Andalus, had just begun his reign and had placed a new emphasis on the importance of the Islamic arts.

Ziryab then rose to prominence, became the chief entertainer of the court of Cordoba, and was happily encouraged to experiment with Islamic music.

While Ziryab was multi-talented, it was his skill with the oud that set him apart. He redesigned the instrument, adding a fifth bass string to increase its musical range, and discarded its wooden pick in favour of an eagle’s feather.

Ziryab also placed the oud at the centre of the curriculum for the major music college he established in Al-Andalus. This college fostered musical experimentation. Ziryab fused Islamic instruments, music and dance with those from Spain. This work was carried on by his eight sons and two daughters. Some historians credit these efforts with the birth of the Spanish guitar, evolved from Ziryab’s oud, and the emergence of flamenco music in Southern Spain.

It is widely believed that this golden era of oud music in Al-Andalus, led by Ziryab, prompted a boom in the popularity of the instrument in Northern Africa.

I had forgotten the story of Ziryab that I read in Seville until I came across a handsome North African oud on display in the Musical Instruments Museum, in Brussels. Made in Alexandria, in the early 1800s, that instrument had seven double strings, as was common with Egyptian ouds from the 19th century. Kuwitra is the name typically used for the oud in Northern Africa, while it is often called a lavta in Balkan nations such as Albania and Macedonia.

Throughout each of these areas in which the oud is prevalent, its function within music is relatively uniform. It has long been a key element of Arab orchestras and is also often played in smaller bands or solo. This latter mode represented my first experience with hearing the oud live. I had booked a trip to Morocco and, despite my familiarity with its history, had never heard the esteemed instrument played, so was intent on meeting an oud musician in the flesh.

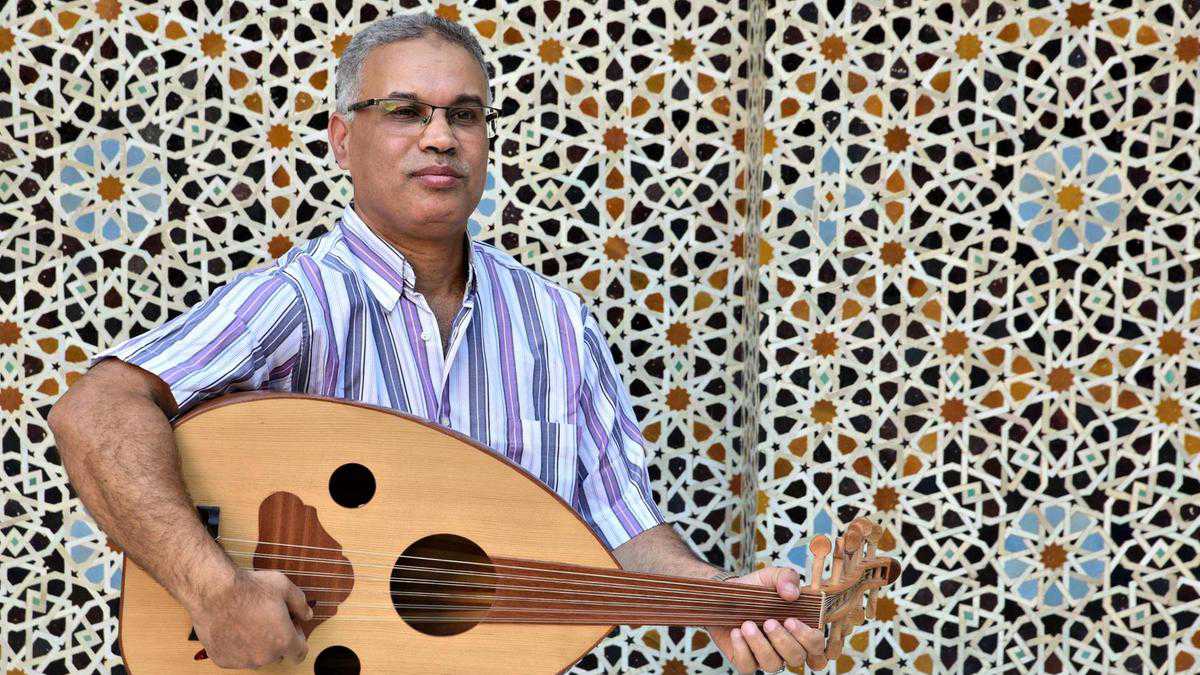

Sitting on that rooftop terrace in Fes’ old town, Mohamed Semlali is strumming this ancient instrument. So deep is he in concentration that, even after I sit opposite him, a few seconds elapse before he notices my presence.

As I compliment his playing, Semlali lowers his gaze and shakes his head shyly, as if he is trying to shrug off this praise. When I follow up with a commendation of the oud he looks back up at me, his face and eyes smiling, and nods with enthusiasm. Then he stops playing and taps his guitar like an old friend. He points at the instrument and, through an interpreter, explains he feels lucky to have it. “This is special,” he says of his oud, looking out across the rooftops of this historic city.

Aged in his fifties, Semlali has played the oud since he was a young man. It is an extension of his body, of his mind and of his soul. For many years now, he has offered oud tuition to local children and adults, something he sees as a good deed, as a means of protecting this invaluable piece of Arabic musical heritage.

Recently, he has also started offering lessons or demonstrations to foreign tourists. This is how we meet. I tell Semlali that I am bereft of musical talent. Even the bongo drums are too complicated, I joke, prompting a hearty laugh. But he is not discouraged. The polite, neatly dressed man patiently shows me a few of the basics – how to hold the oud solidly, how to pluck its strings gently yet with intent, and how to position my fingers along its sleek neck.

But I have not come here with aspirations to become the next Ziryab. I do not need to know how to play the oud. I just want to hear it. Semlali has no problem with this and ushers me down from the terrace and out of the restaurant to an altogether more evocative setting.

We are all alone in the courtyard of a stunning 14th-century Islamic college called Bou Inania Madrasa. With its marble floors, mosaic walls and intricate woodwork, it could not be more attractive. At least, that’s what I think until Semlali begins playing. As I had suspected, the sound of the oud makes the world a more beautiful place.