South Korea spycam crimes put hidden camera industry under scrutiny

28 March, 2019

Shin Jang-jin's shop in Incheon offers seemingly innocuous household items, from pens and lighters to watches and smoke detectors, but with a secret feature - a hidden one millimetre-wide-lens that can shoot video.

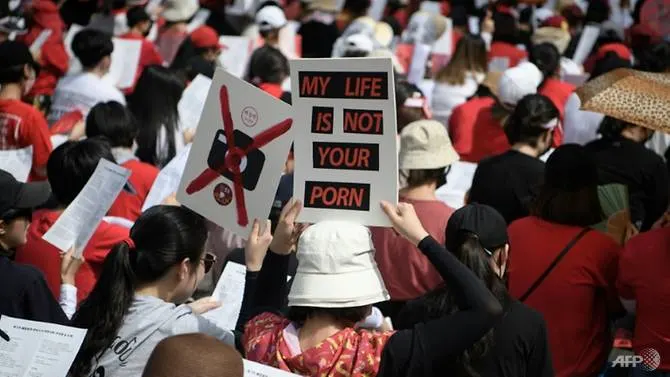

Over the past decade, Shin has sold thousands of gadgets. But his industry is coming under pressure as ultra-wired South Korea battles a growing epidemic of so-called "molka", or spycam videos - mostly of women, secretly filmed by men in public places.

Shin insists his gadgets serve a useful purpose, allowing people to capture evidence of domestic violence or child abuse, and told AFP he has refused to serve customers looking to spy on women in toilets.

"They thought I would understand them as a fellow man. I turned them away."

But the 52-year-old admits he is not always able to spot unscrupulous buyers.

In 2015 he was questioned by police after one of his products - a camera installed inside a mobile phone cover - was used to secretly film women in a dressing room at a water park outside Seoul.

He had sold the device to a female customer and said he had no idea she would use it to film and distribute illicit footage online.

Under current regulations, spycam buyers are not required to give personal information, making it difficult to trace their ownership and use of the devices.

But some lawmakers are hoping to change that, co-sponsoring a bill in August that requires hidden camera buyers to register with a government database, raising alarm among retailers like Shin.

CRIME SURGE

Spycam crimes have become so prevalent that female police officers now regularly inspect public toilets to check for cameras in women's stalls.

In one case, offenders had livestreamed footage of around 800 couples having sex - filmed in hotel rooms using cameras installed inside hairdryer holders, wall sockets and digital TV boxes.

As well as secretly filming women in schools, toilets and offices, "revenge porn" - private sex videos filmed and shared without permission by disgruntled ex-boyfriends, ex-husbands, or malicious acquaintances - is believed to be equally widespread.

In a burgeoning scandal that has shaken South Korea's entertainment industry, K-pop star Jung Joon-young was arrested this month on charges of filming and distributing illicit sex videos without the consent of his female partners.

The number of spycam crimes reported to police surged from around 2,400 in 2012 to nearly 6,500 in 2017.

According to official statistics about 98 per cent of convicted offenders are men - ranging from school teachers and college professors to church pastors and police officers - while more than 80 per cent of victims are women.

MALICIOUS INTENTIONS

"I turn customers away when it isn't clear why and what they want hidden cameras for," Lee Seung-yon, who customises spycam gadgets in Seoul, told AFP.

But he admitted his approach was no guarantee against crimes.

With the bill currently under consideration by a parliamentary committee, gadget retailers like Shin fear it will turn away potential customers.

"More than 90 per cent of spycam porn crimes are due to mobile phones, not specialised items," he said, adding that any crackdown on the gadgets was akin to blaming knife makers for knife-related murders.

While there is no official data to support Shin's claim, a police official told AFP that "most" spycam footage is taken using smartphones.

But women's rights activists say the claim is "misleading", citing numerous cases involving customised cameras.

Furthermore, they argue that since smartphones sold in the South are required to make a loud shutter noise when taking pictures - a measure put in place to combat spycam crimes - many offenders deploy high-tech devices or use special apps that mute the sound to secretly film victims.

"Victims in most spycam crimes realise they were filmed only after illicit footage had been shared online whereas crimes involving mobile phones are much easier to catch in the first place," said Lee Hyo-rin of the Korea Cyber Sexual Violence Response Center.

"The solo purpose of these gadgets is to deceive others," she told AFP.

TAG(s):