The generous Middle Eastern tradition of istiftah lives on in Iraq

16 February, 2021

As sunlight rises over Erbil’s historic bazaar, shopkeepers sweep their stoops and eagerly await the istiftah, the initially customer of your day, believed to be a good omen.

For a country as famously hospitable as Iraq, where lunch tables are often filled with platters of meats as large as truck tyres, the custom of istiftah, this means “opener”, is subtle but sweet.

The first customer of your day gets to name her or his price for the products or service being purchased, without the usual procedure for haggling and compromise that is quintessential to street market segments.

“The first customer is exceptional,” said Hidayet Sheikhani, 39. “He’s carrying riches and well-being direct from God to the businessperson in the first morning.”

Sheikhani markets traditional black-and-white colored embroidered scarves and hats in the bazaar on the bustling centre of Erbil, the Kurdistan region’s capital.

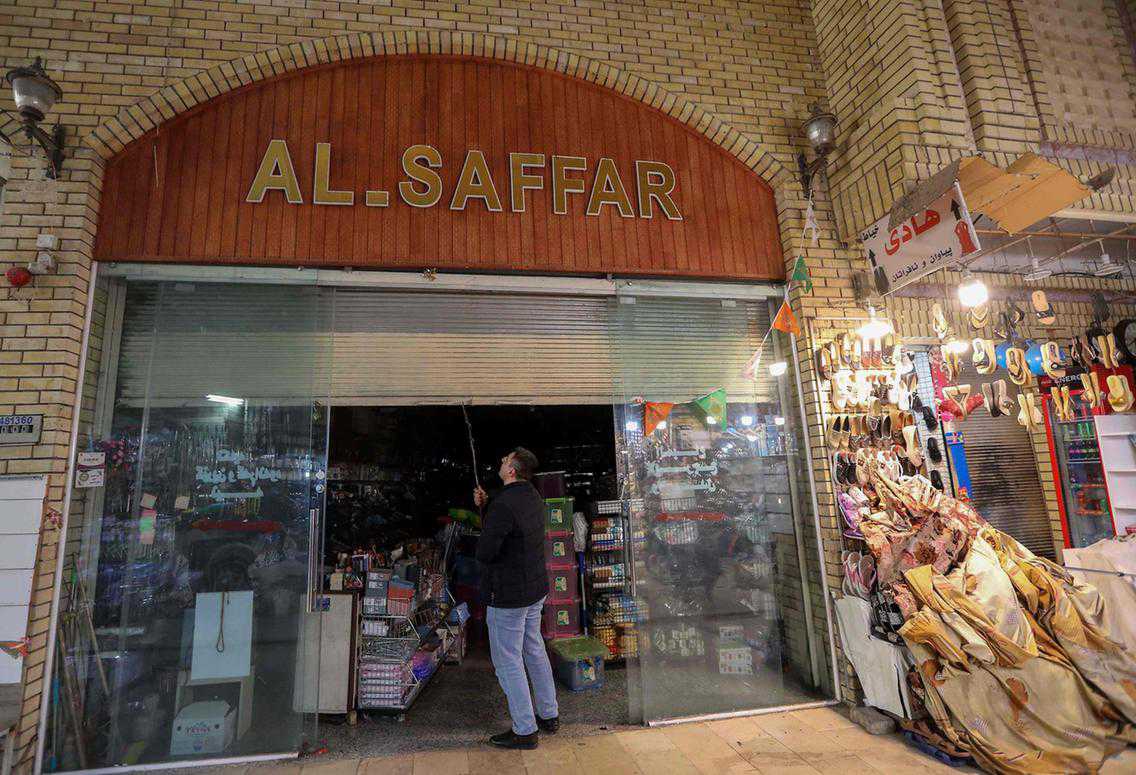

Shopkeepers get to the bazaar’s brick alleyways in about dawn, roll-up the metal shutters of their shops and pour a great obligatory glass of lovely tea to get started on their day.

It’s a traditions as old as time, not merely in Iraq, but across the Middle East.

Sheikhani inherited it from his grandfather, who had a good shop found in the same market place a century ago.

At that time, he stated, the istiftah tradition set the tone for the rest of the day.

Shopkeepers who hadn't yet sold anything would place a chair outside their shop, seeing that a sign to their colleagues.

Those that had made their first sale would direct any incoming shoppers to the other shops, until everyone had had their istiftah.

Only in that case would they accept another customer.

That went for both Muslim and Jewish shopkeepers, said Sheikhani, because Erbil was residence to a thriving Jewish network until the mid-20th century.

‘God can make it up to me’

The foundation of the istiftah tradition remains disputed.

Some say it really is from the Hadith, an archive of what and actions related to the Prophet Mohammed, in which he pleads to God, “Oh Allah, bless my persons within their early mornings”.

But Abbas Ali, a lecturer at the College of Islamic Analyses in Iraq’s Salahaddin University, said the custom’s prevalence among persons of different faiths indicates it might not exactly be linked to Islam at all.

“It’s possible it was merely an ancient tailor made that was practised for years, and good traditions sometimes become religious rituals,” Ali said.

Either way, it lives on, even among young businessmen.

Jamaluddin Abdelhamid, 24, and sporting a wispy goatee, offers roasted nuts, sweets and spices in the bazaar.

“Often, a customer requests honey because they’re sick. It usually costs 14,000 Iraqi dinars (significantly less than $10) per jar, nonetheless they require it at 10,000 and I concur because it’s the istiftah,” he said.

“I know God can make it up to me somewhere else in my own day.”

Rejecting a first customer’s request, regardless of how steep the low cost is normally, leaves him guilt-ridden.

“I spend all day every day sense sad, asking myself how I could have rejected God’s blessing,” Abdelhamid said.

Tradition under threat?

It goes beyond the old bazaar: even taxi drivers and tradesmen have adopted it.

“Whatever cash I earn first per day, I kiss it and increase it to my forehead as an indicator of gratitude to God,” said Maher Salim, 46, a car mechanic.

But an istiftah by no means goes free of charge.

First customers often offer a very discounted price because of their early-morning purchase, but it’s frowned after to request something free at all.

“Also if it’s my brother, I’ll have something symbolic from him, even just 1,000 Iraqi dinars,” Salim said.

There’s 1 creeping threat to the beautiful balance of the istiftah: malls.

As Erbil has developed over the past decade, large looking centres have cropped up over the city, supplying convenient and speedy retail experience to its residents.

Mohammad Khalil even so buys his groceries, bread, yoghurt, cheese and fruit and vegetables each morning from small shops close to his home, showering the shopkeepers with prayers for blessings and very good health as he walks away.

Interactions in malls, he complained, are actually comparatively cold.

“There’s no sense of istiftah there, everything is about the computer program,” Khalil said.

“More often than not, the persons who work in the mall retailers aren’t the actual owners, as a result they don’t even value the tradition.”

Source: www.thenationalnews.com

TAG(s):