Genetic atlas reveals microbial fingerprints of the world’s cities

29 May, 2021

“If you gave me your shoe, I could tell you with about 90% accuracy the town in the world that you came,” says Christopher Mason, Ph.D., a professor at Weill Cornell Remedies in New York, NY.

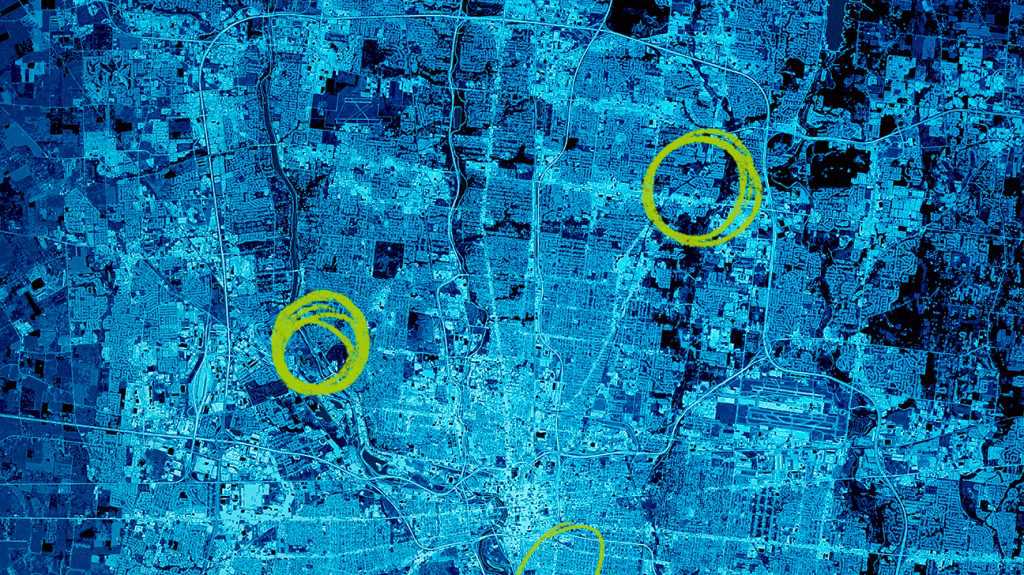

Prof. Mason and collaborators around the world swabbed railings, chairs, and ticket kiosks on bus networks and subways in 60 cities.

Over three years, the scientists collected 4,728 samples and sent them to a lab at Weill Cornell Medicine for analysis.

The laboratory used a method called shotgun metagenomic sequencingTrusted Source to recognize 4,246 known species of urban microorganisms from their DNA.

In addition they found 10,928 viruses, 1,302 bacteria, and two archaea that were unknown to science.

They discovered that each city includes a unique microbial fingerprint, likely as a result of distinctions in climate and geography. In addition, there is a “core” group of 31 species that aren't found in our body but cropped up in 97% of all the samples.

The scientists have published their findings - that they describe as the “first systematic, worldwide catalog of the urban microbial ecosystem” - in the journal Cell.

They write that each day, vast amounts of the people who stay in cities come into contact with surfaces in mass transit systems, such as for example subways and bus networks.

Travelers bring with them the harmless “commensal” microbes that stay in and on the bodies and come into contact with the organisms already found in the environment.

This allowed the researchers to use the collective microbial genome or “microbiome” of mass transit systems as a proxy for the urban microbiome as a whole.

Swabbing the subway

Prof. Mason began collecting and examining microbial samples from the New York City subway in 2013.

When he published his initial findings, researchers from all over the world began to contact him, requesting advice about surveying their own metropolitan areas.

Prof. Mason created a protocol to standardize the sampling so that, for example, each study included swabs from benches, handrails, and the counters of ticket booths - spots where travelers either be seated or set their hands.

“[T]hese will be the most ‘high feel’ surfaces generally in most towns, and we wished to also have spots that would be uniform across the sampled places,” Prof. Mason explained to MNT in an email.

The most recent study revealed that lots of several bacterial genes that confer resistance to common antibiotics are widespread in the urban environment.

The most typical resistance genes that the researchers determined allow bacteria to survive contact with two main classes of antibiotics, known as MLS and beta-lactam antiobiotics.

Healthcare professionals work with these antimicrobials to take care of respiratory, sexually transmitted, and skin diseases, among many other infections.

Source: www.medicalnewstoday.com